FACE TIME: Kent Artist Joel Ely on identity and the stories we tell

“I wanted to sort of approach those things in a humorous kind of way, with a bit of beauty, a bit of sadness and a bit of comedy.”

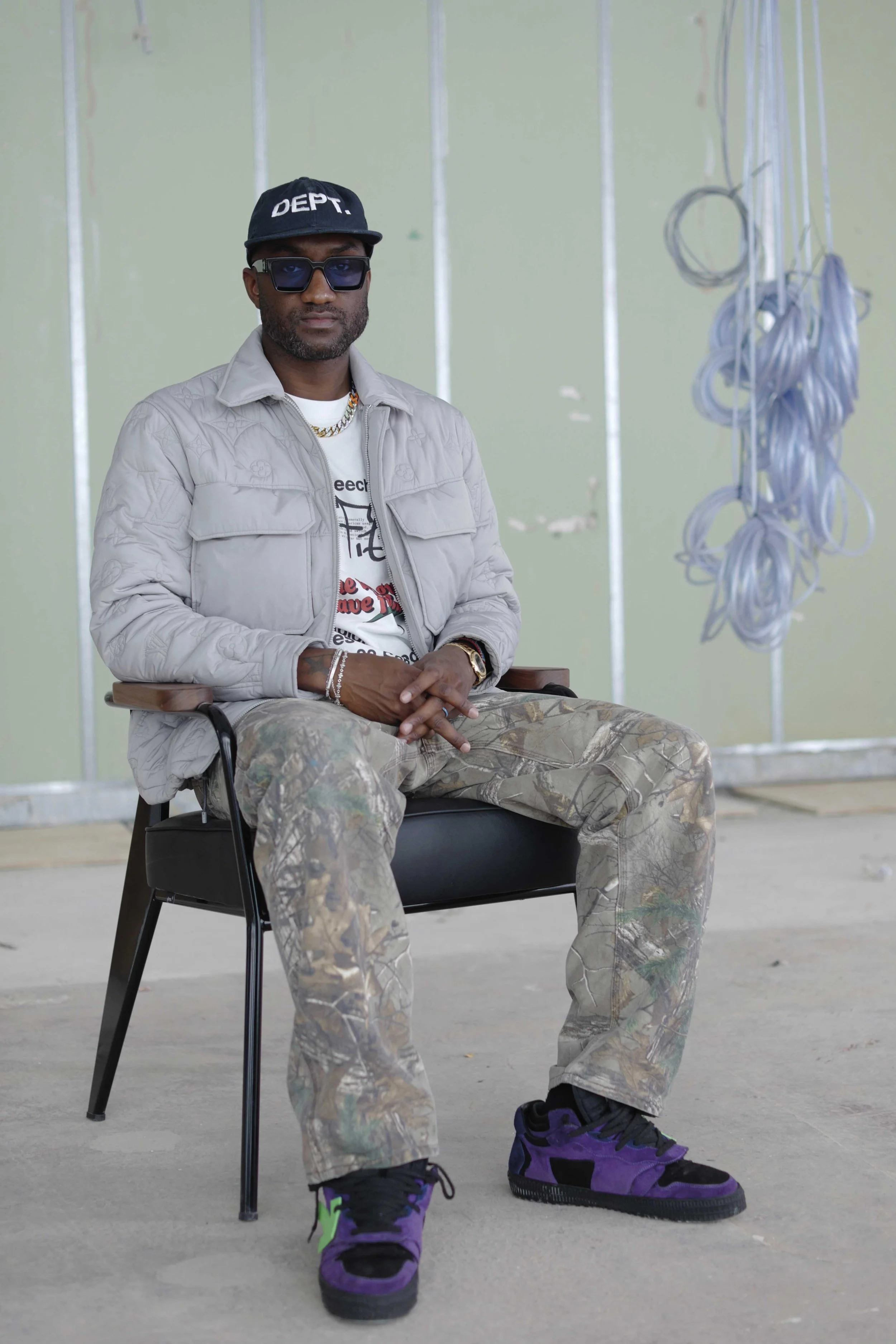

BJ Deakin Photography

In an age of cultural fragmentation and digital uncertainty, Joel Ely’s (@joel_ely_art) art speaks to questions of identity, tradition and progress. Varying from the ultra-real and deeply human to sculpture with diverse and layered meaning, Joel’s work has the ability to provoke, unsettle and delight - often all at once.

Having lived between Maidstone and Faversham - and studied in Canterbury - for much of his life, his Kentish roots are central to his creative outlook. “I feel like, especially Kent - but England in general - is dealing with a difficult point in time,” he says. “We need to have a conversation that’s pointed and specific but open to everyone. The complexity and breadth of our identity needs to be acknowledged.”

Identity is too easily pigeonholed, but Joel’s art, whether portrait, sculpture or still life, works to open that conversation.

Joel’s recent projects - particularly his contributions to the Storytellers exhibition at the Beaney in Canterbury and the ongoing Great Expectations series - bring Kent’s layered history into vivid focus. His sculpture Hooden Horses (3 Men of Kent) sits at the heart of these explorations. “I’ve been obsessed with hooden horses since I was five or six,” he says. “I just found these things amazing and then looking into the story about the rural moving into towns economically, and where that came from. I felt that was quite a good way to look at divisions and about movement in Kent.”

From folk rituals to fractured modernity, Joel uses the local to access the timeless. Coming works will draw connections between England’s agricultural revolts such as the Swing Riots in 1830 and today’s anxieties around AI, automation and technology replacing labour. “With what’s going on with AI at the moment, or even just technology replacing workers, the concerns of people trying to make a living have continued again and again. So there’s nothing new in that,” Joel says. “We’ve been dealing with that for 2,000 years, at least.”

This thread of resistance and reinvention also runs through the Great Expectations series, which Joel describes as a set of ‘mini-monuments’ to Kent. The project channels narratives of aspiration, anarchy, conservatism and innovation from the Stone Age to the present.

From cherrywood sculptures paying tribute to the National Fruit Collection (Brogdale) to a portrait of Second World War pilot Squadron Leader Mahinder Singh Pujji (Gravesend) and

The Lioness and the Unicorn, which features the shirt of England footballer Alessia Russo (Bearsted) alongside the first edition of George Orwell’s Book The Lion and The Unicorn.

“Originally it was just gonna be the three horses and then it evolved from there. There was so much news, you know, Alessia Russo winning the Euros at the time, and the fact that she’s the granddaughter of migrants from Sicily. It’s an incredible story and something we should all be proud of from Kent and in England.”

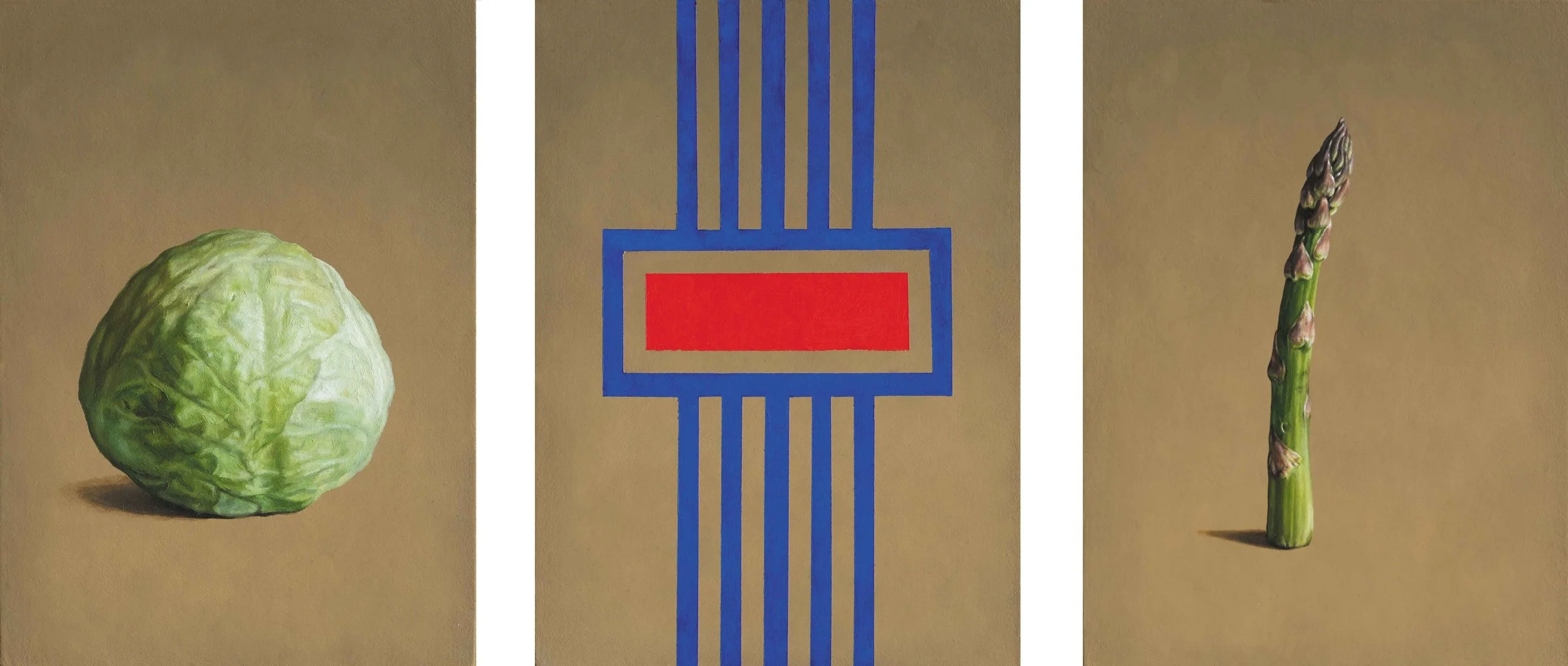

REALISM

That balance between reverence and ridicule is typical of Joel’s style. His self-portrait that features his head laid among vegetables in a strikingly realistic still life is a great example. “There’s three layers to it,” he explains. “The cost-of-living crisis, the legacy of Covid and the personal story of nursing my father at home. It’s like a tomb effigy and a supermarket conveyor belt… I wanted to sort of approach those things in a humorous kind of way, with a bit of beauty, a bit of sadness and a bit of comedy.”

That human element is vital to Joel’s approach to his portraiture. Though commissions help sustain him financially - alongside work as an artist’s assistant - he views them as more than just income. “I want to get at some truth about the person, an honesty. I truly hope that they look like the person on a good day, rather than like an airbrushed swagger painting.

“High-society portraits are fine, but that’s not what I do. I much prefer that sort of slightly awkward, human, kind of intensity. I sit with people. I do studies from life, I talk to them, go to their places of work, you know, try to get to know them a bit.”

Ely’s commitment to sincerity and complexity also informed his 10-painting commission for New College, Oxford, now nearing completion. The series, focused on non-academic staff like chefs, housekeepers and librarians, honours people often left out of grand institutional narratives. “They’re not just ‘support staff’. These are the people who make the place work.”

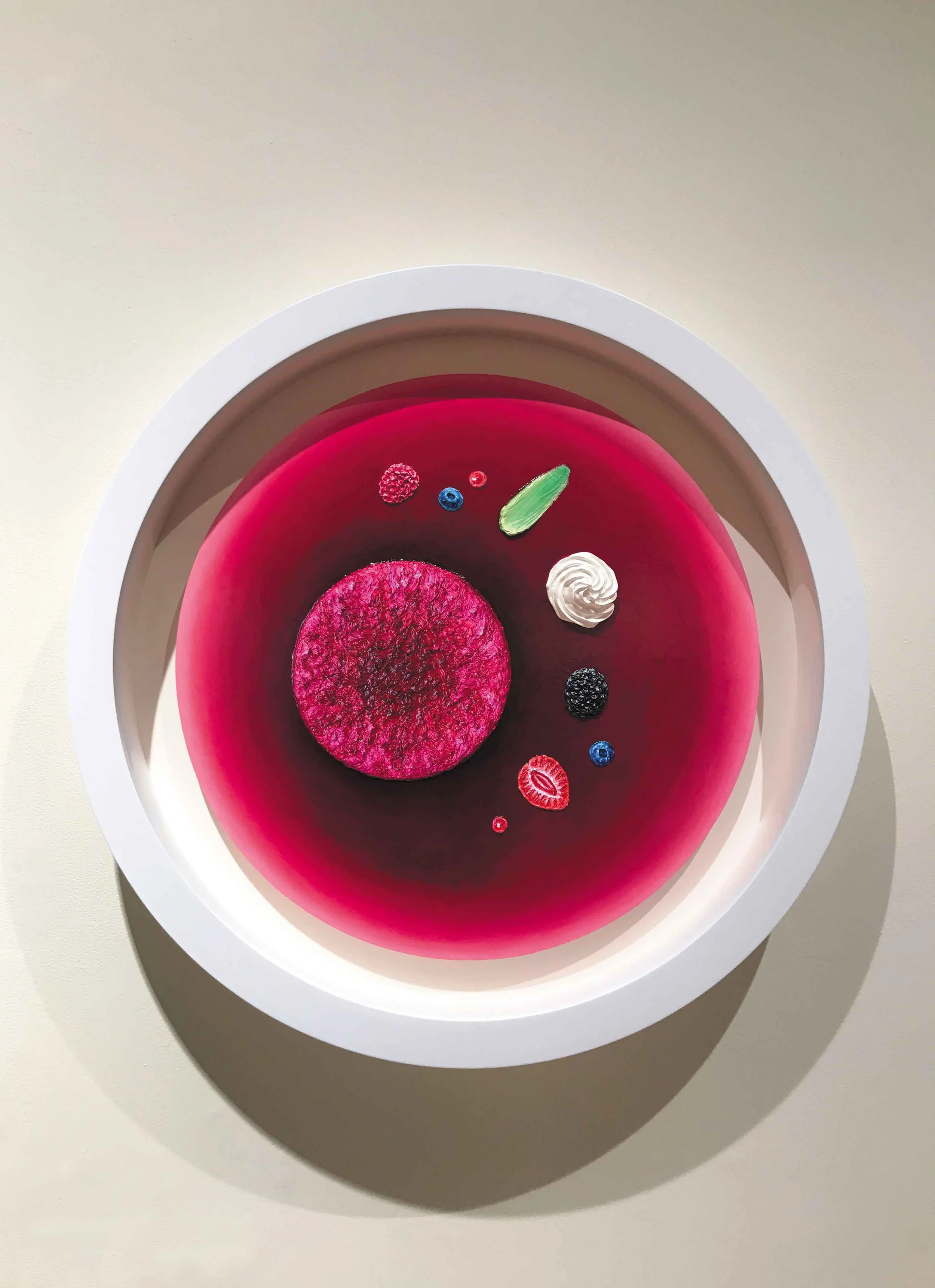

Beyond Kent, Ely’s curiosity and commitment to cultural specificity have taken him to Spain’s Basque country, where he explored themes of food, tradition and nationalism through time spent at Txoko Mallona, one of Bilbao’s oldest gastronomic societies. “Food and figurative art have a shared language,” he says. “Anyone can talk about them. They’re accessible, but there’s no easy answer. That’s the best thing art can do.”

Whether it’s a meticulously rendered still life, a folkloric sculpture or a quietly revealing portrait, Joel’s art is ultimately about people: who they are, how they live and what they carry with them. His home county, with its blurred boundaries between rural and urban, tradition and change, offers endless inspiration and challenge.

Joel says: “The stories we tell about ourselves, the stories others tell about us, and the stories we tell about others.”

INFO: www.joelely.com