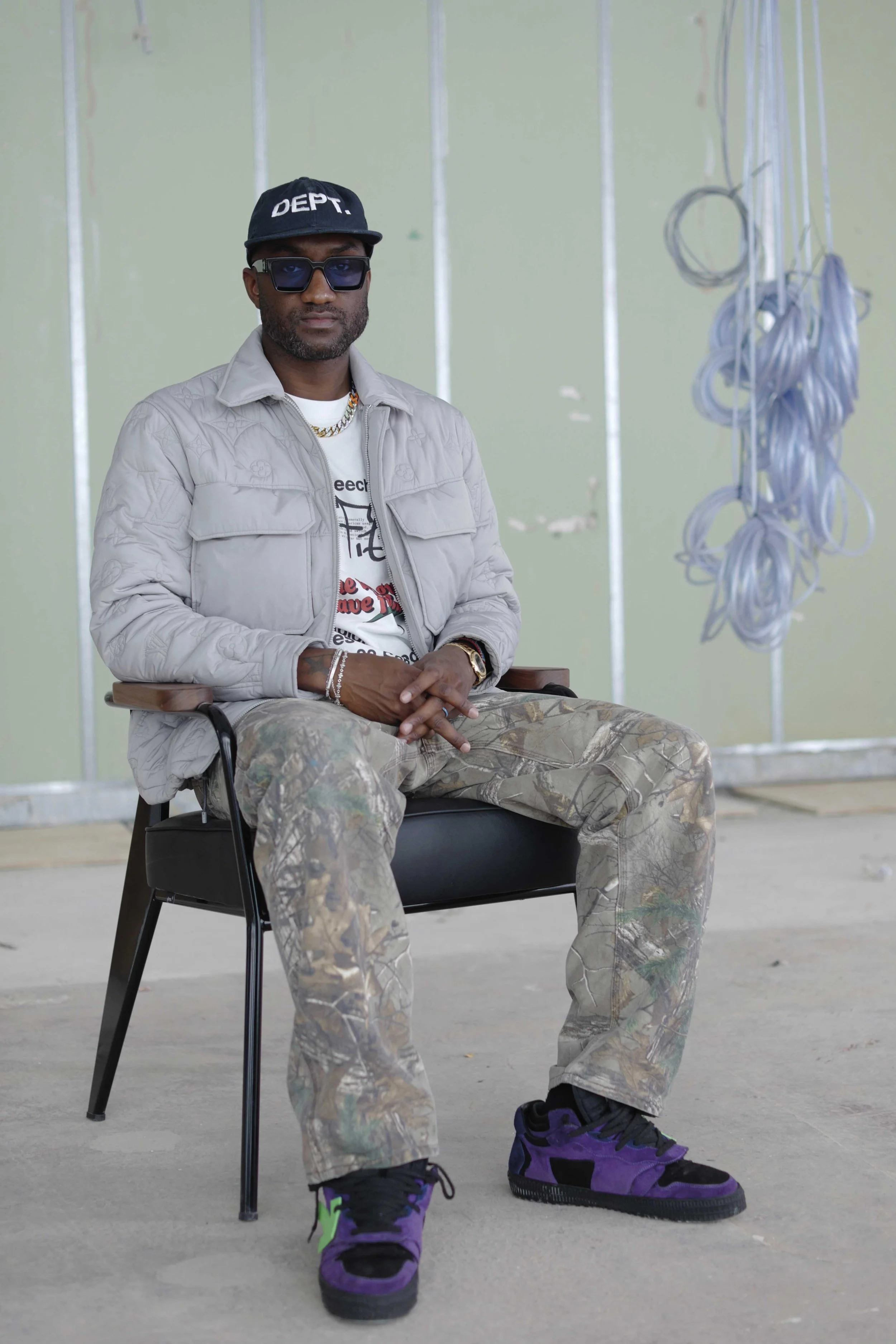

MOTION COLOUR SCENE: Artist Phillip Long

Whitstable artist Phillip Long on how a psychedelic past still shapes his vibrant artwork of the present

In the early 1990s, the UK’s underground rave scene was more than just a dance floor - it was an explosion of rebellion, energy and artistic expression. For one artist, it was also the unlikely beginning of a decades-long creative journey that’s taken him from squats in south London to trance festivals in South Africa, from psychedelic canvases in Quebec to sleek art galleries in Margate.

Now entering the more traditional art world, Phillip Long, aka Nagual Creations (@nagualcreations), was known in the 90s club scene for his large-scale UV backdrops and immersive installations but has finally brought his past and present into one space, showing how the visceral, visual intensity of rave culture still pulses through his brushwork today.

After dropping out of art college at 17, he left art behind - at least for a while. But in the early 90s, the rave scene pulled him back in.

“I was always into drawing and creating,” he explains. “And then I discovered raves. At first, it was the UV that grabbed me. The impact of fluorescent colours in the dark, it was really powerful. But the novelty wore off pretty quick. It was all just acid-house smileys and flying saucers. I remember thinking ‘They’re missing a trick here’.”

That thought became action. A chance comment on a neighbour’s business card led to him painting a dreadlocked character on a sheet for a shop window. That banner sold for £100, then caught the eye of a local record store. They hired him but with one piece of advice: “You shouldn’t be selling these - you should be renting them to clubs.”

“I hated my job,” he laughs. “Within a month, I quit. I had about six massive paintings and I immediately started getting booked to do warehouse parties.”

The momentum was instant. His art - huge, immersive, UV-reactive canvases - turned cavernous, empty warehouses into otherworldly environments. He and his wife began producing their own events, using any space they could find.

“Photographic studios, weird places,” says Phillip. “They weren’t even clubs half the time. It was just built with word of mouth. But my philosophy was always: if you walk into an empty space, it’s soulless. Fill it with colour, structure, story - give people a proper experience.”

Soon, the parties grew. Too much, in fact.

“As soon as they got to a big size, we didn’t like it. I’ve never been commercially minded - it’s always been about the atmosphere, the experience. Once the Criminal Justice Bill came in, it became really difficult to put on events legally.”

The couple then moved into a warehouse themselves, transforming it into a live-work space- and a secret venue.

“Half was my studio, the other half living space. Once a month, we’d shove everything into the bedrooms. The studio became the dance floor, the living room the chill-out, kitchen the bar. Invite-only. That was the vibe.”

But as word spread, bigger names came calling. Ministry of Sound, Heaven, Megatripolis, each venue commissioning his decor. He’d create on instinct, arriving with a van full of visual magic and transforming a venue with no brief.

“It was trippy and eclectic. I’d do Turnmills on a Friday, then a sweaty dive in Brixton the same night.” Soon, his work reached beyond the UK. A spread in The Sunday Times Culture Magazine opened international doors and he began touring across Europe, Japan, South Africa, Canada and the US, all while lugging 80kg of rolled canvases through airports.

“I’d built custom waterproof carriers. The paintings would roll up, but sometimes I had to ship massive crates. I even built collapsible 3D installations that I could rebuild on site. One dragon was 30 feet long and fit in a suitcase.”

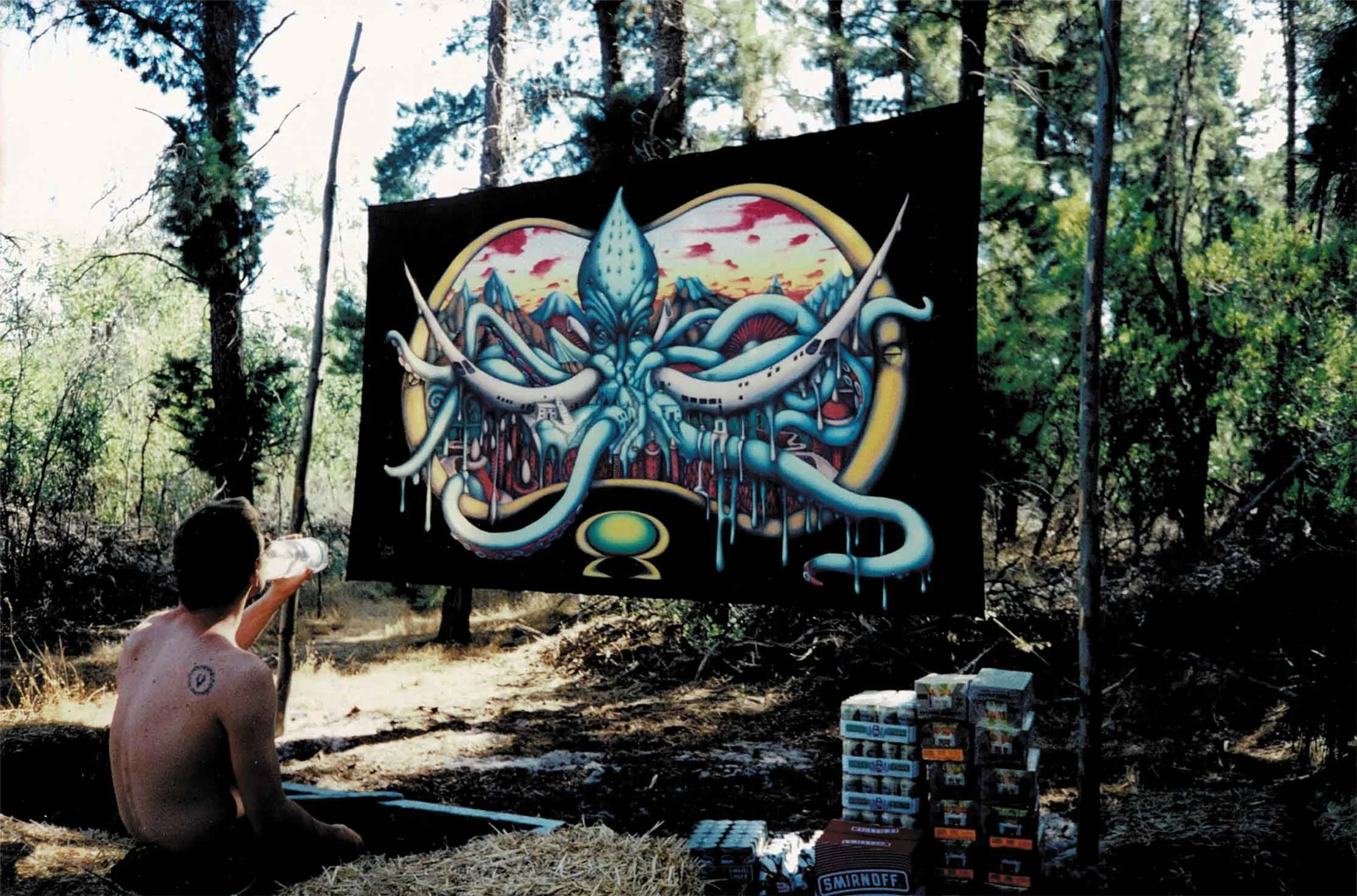

A staple of the trance music scene, Phillip was even called in to design festival-stage artwork. He recalls one gig in particular, a psychedelic trance party on an ostrich farm in South Africa.

“I’ve got a photo of me just after setting up, smoking a cigarette in the bush, this big UV painting hanging behind me. Totally surreal.”

Eventually, the high-octane lifestyle gave way to real-life responsibilities. After the birth of his first son, he moved back to the UK and took a detour into the corporate world, becoming an art director in the world of banking.

“For five years I was in suits, offices, meetings… one day I looked around and thought ‘A few months ago I was in a trance party on an ostrich farm and now I’m in Dubai in a boardroom at Thomson Reuters’. It just wasn’t me.”

He left the job, went back to painting full-time and started showing his work in galleries. But there was a disconnect - he was almost like a new name in the art world despite decades of global recognition in underground scenes. After moving to Whitstable, Phillip began looking to unite his past and present, and headed the Pie Factory Gallery in Margate - the perfect place to exhibit his new fine art alongside the UV rave installations that put him on the map.

“I wanted people to see the reverberations of the rave scene in what I’m doing now. The front was for contemporary work, prints, oil paintings - stuff you could live with. The back rooms were completely blacked out. UV everywhere. Full immersion.”

While some of the canvases he showed had travelled the world - still bearing insect remains from gigs in the South African bush or Indian reservations in Quebec - his work today still provokes conversation and draws in the viewer.

“Ultimately, I want my art to be enjoyable to anyone,” says Phillip. “The kind of thing you look at once and go ‘Wow!’, then come back and find something new every time.”

He paints with oils, entirely by hand, achieving such fine detail that people often assume the work is digital or even AI-generated.

“It’s not surrealism, it’s not realism, it’s not abstract… I don’t really know what it is. I guess it’s illustrative with a trippy edge. I want it to grab you viscerally and then invite you into a journey.”

And it does. It’s a journey from acid smileys to international exhibitions, from rolled canvases to gallery walls - the work has evolved - but it’s never lost its soul. It still beats to the rhythm of a kick drum echoing through an east London warehouse, somewhere deep in the 90s night.

“It all came from music,” he says. “And it still does.”

INFO: nagualcreations.co.uk