HALF IN AND HALF OUT: Interview with legendary photographer Tony Davis

The second life of Tony Davis’s photographic Archive

“Some of the rave images are just a single image… one flash and then gone. I left them alone.”

By the time photographer Tony Davis ( @tonydavisphoto) opened a slightly damp cardboard box in a garage during the first lockdown of 2020, he’d spent years barely thinking about the images inside it.

“I’d kind of not thought about its worth at all, really,” he says.

“There were packs and stacks of boxes of negatives and transparencies. Some of it got damaged… a lot of it survived in a garage, really.” What he found, after decades of teaching, raising children and stepping back from being an internationally roving photographer, was the visual record of a cultural moment that Britain was suddenly hungry to see again.

Davis grew up on a Nottingham council estate, an observant kid who became a participant-observer long before he ever held a press card. Between the northern soul and punk movements, his dedication to being live, there and in the moment started young and only strengthened.

Looking back to the beginning, he says: “Growing up as a kid, I was those people. I was a northern soul boy. I went to Wigan Casino… everything I could see in them was me.”

He began documenting life around him in the 1980s, work that earned him a coveted place on a photography course in Newport, Wales. He didn’t take it. “I turned it down because I had a baby and I was already shooting,” he says. But the pull toward photography never loosened. His early career unfolded in the analogue grind of trains, envelopes and darkrooms. “There was no electronic communication, no emails, no nothing… it was the actual physical delivering of negatives and transparencies and prints.”

He spent the 1990s ricocheting between Nottingham, London and assignments that took him across the world. “There was never anything glamorous about it - all the money would go into rolls of film and the next flights.”

When digital swept through the industry in the early 2000s, Davis, by then the father of three, shifted gradually into teaching. Photography, he says, “died away a little bit because my availability was a lot less”.

But his most enduring work had already been made.

IN DEEP

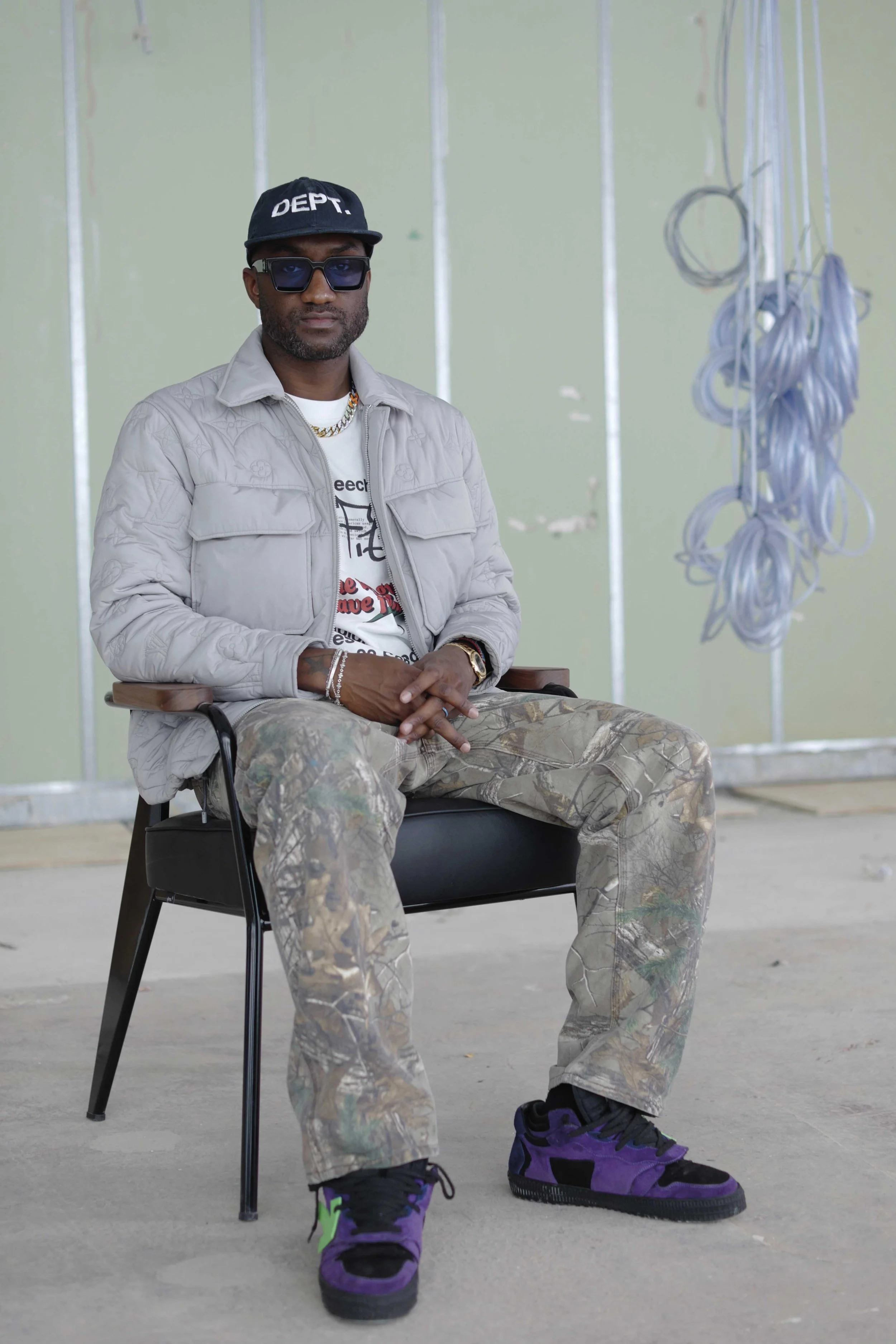

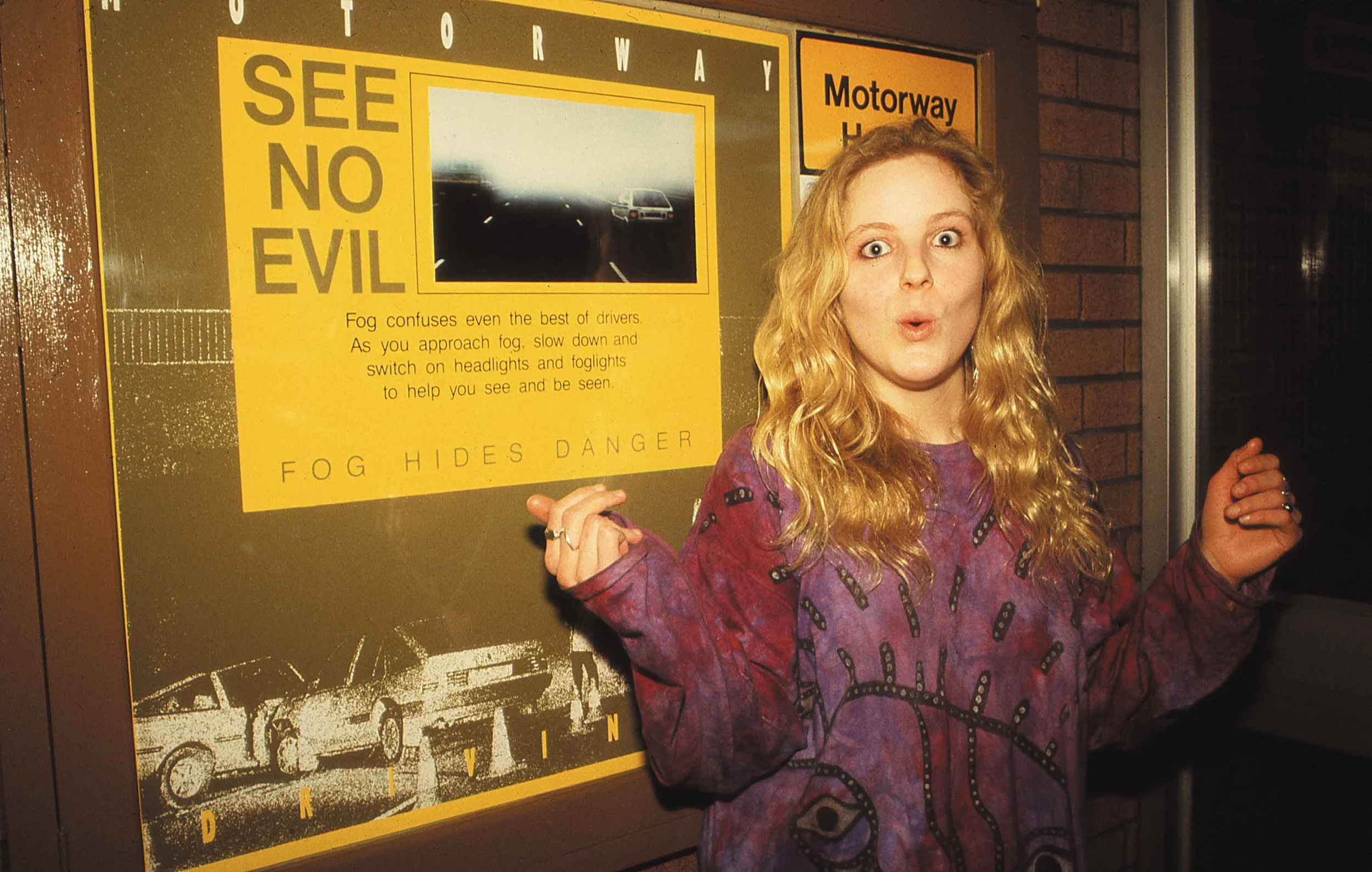

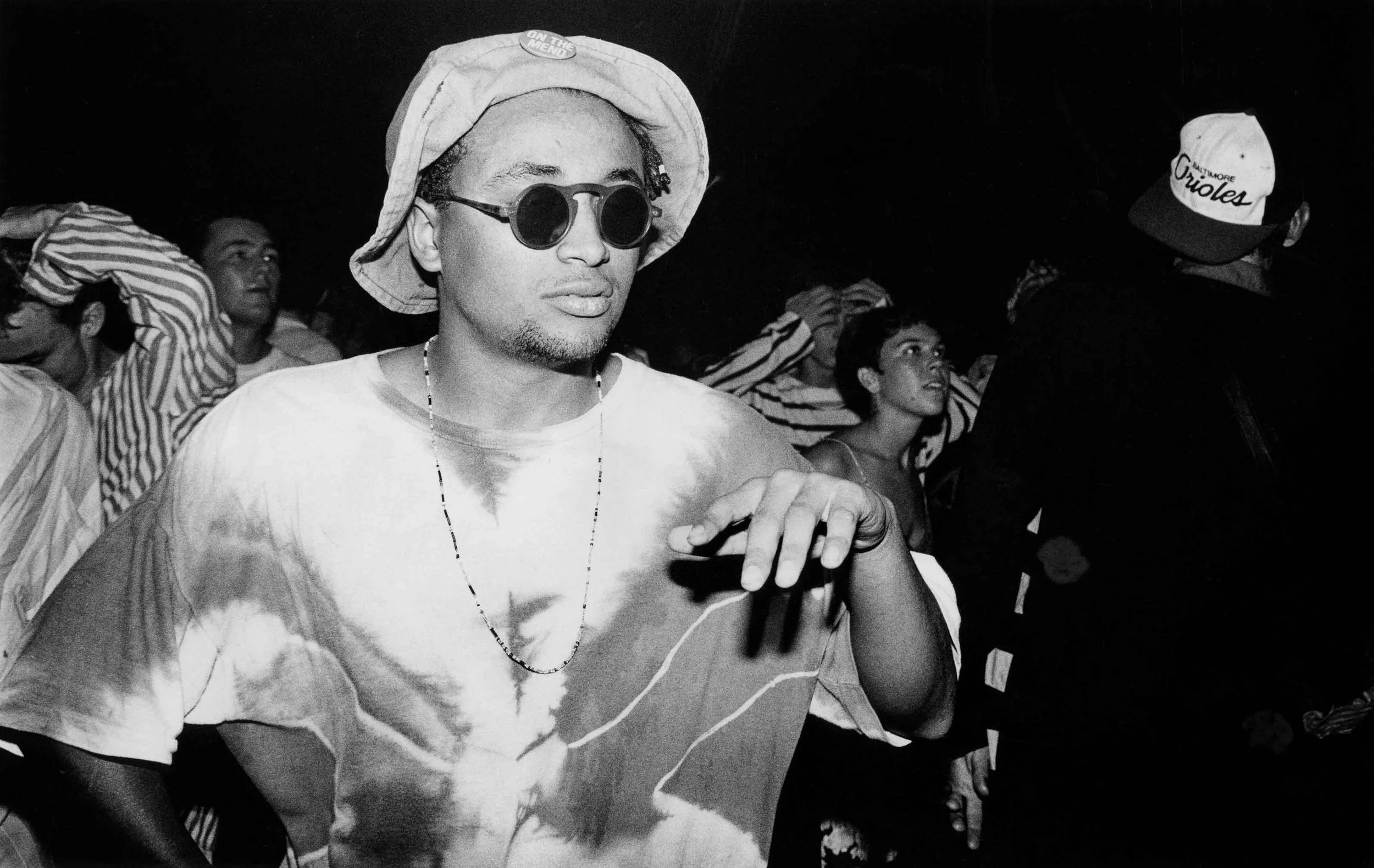

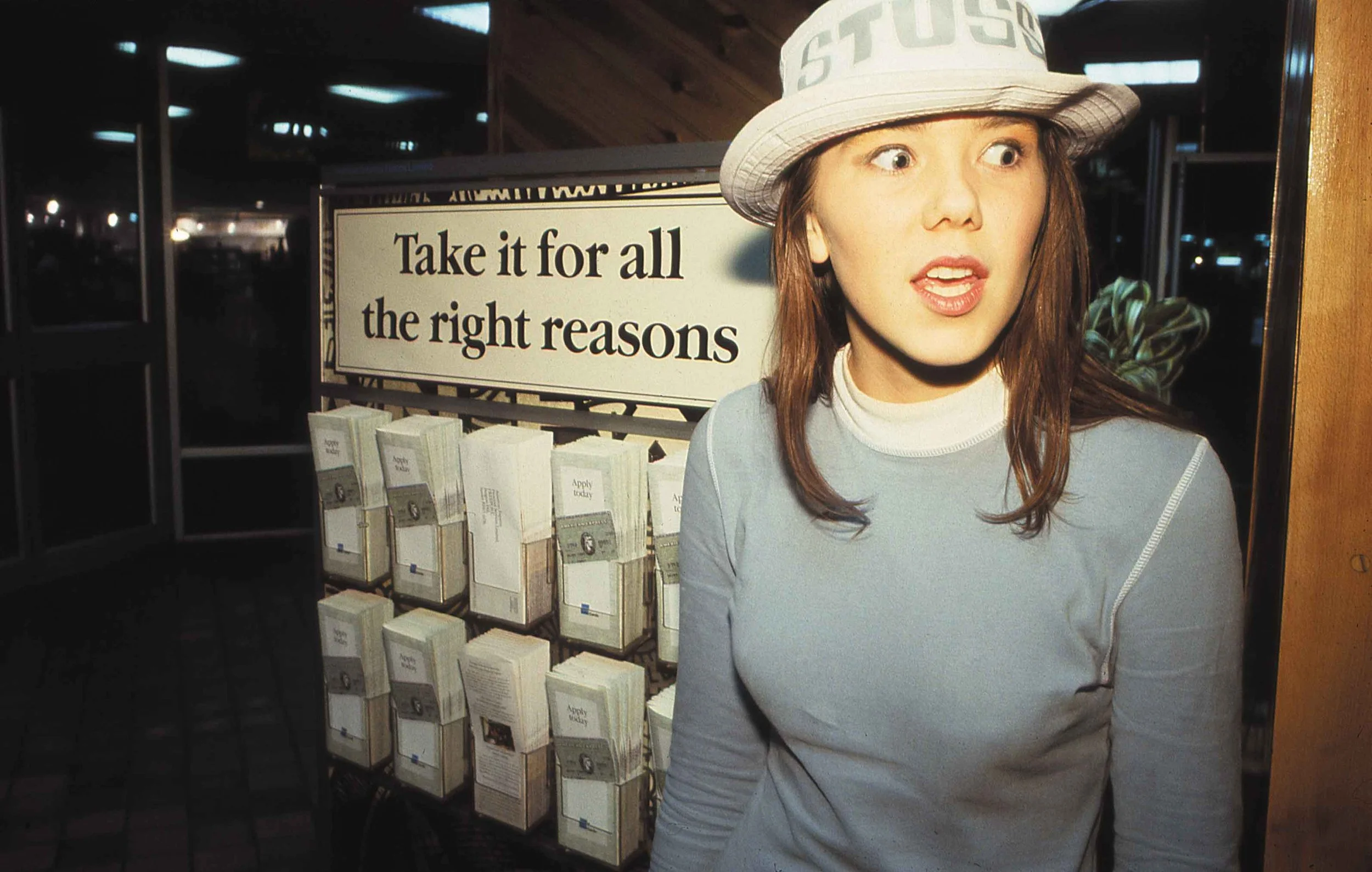

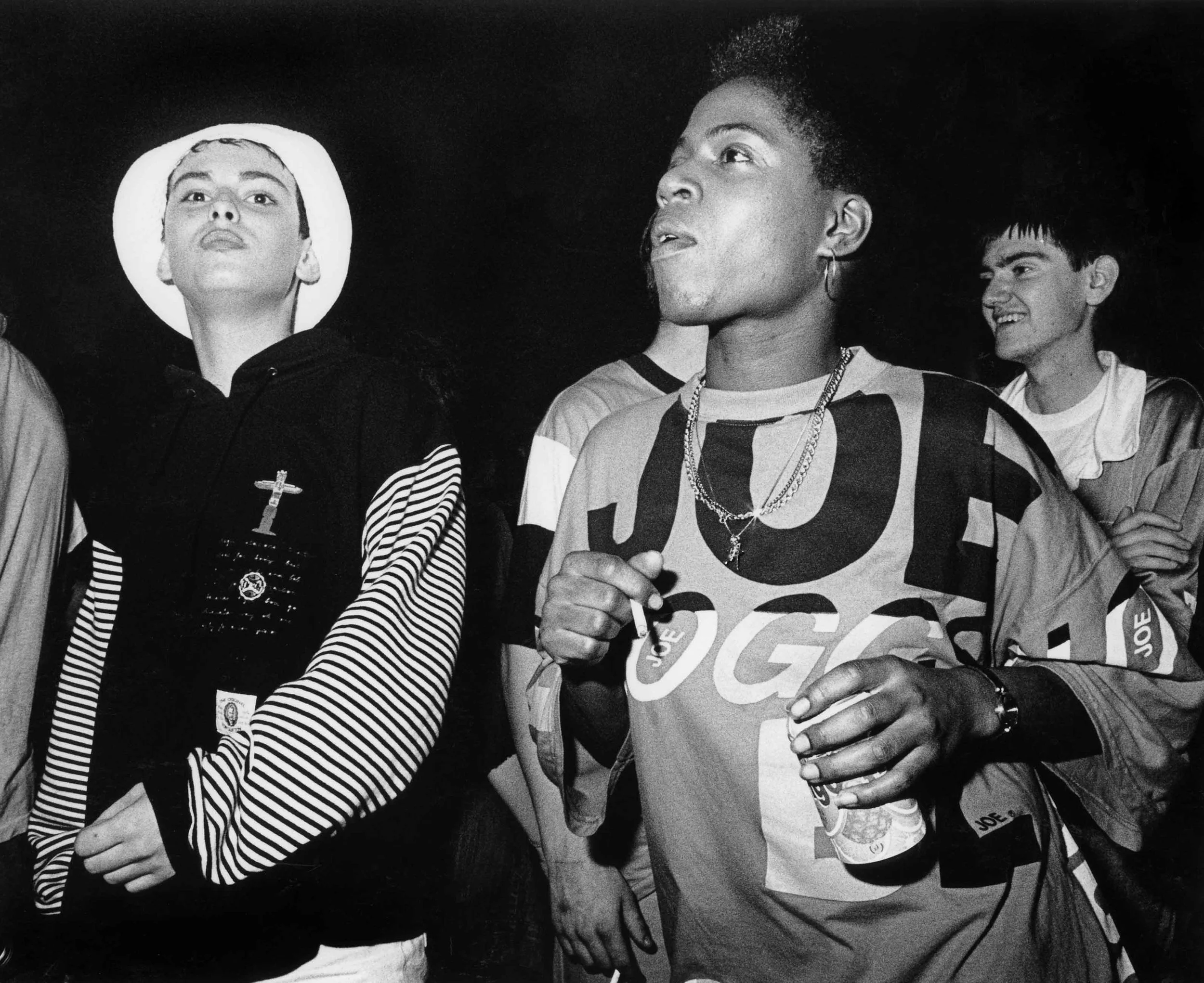

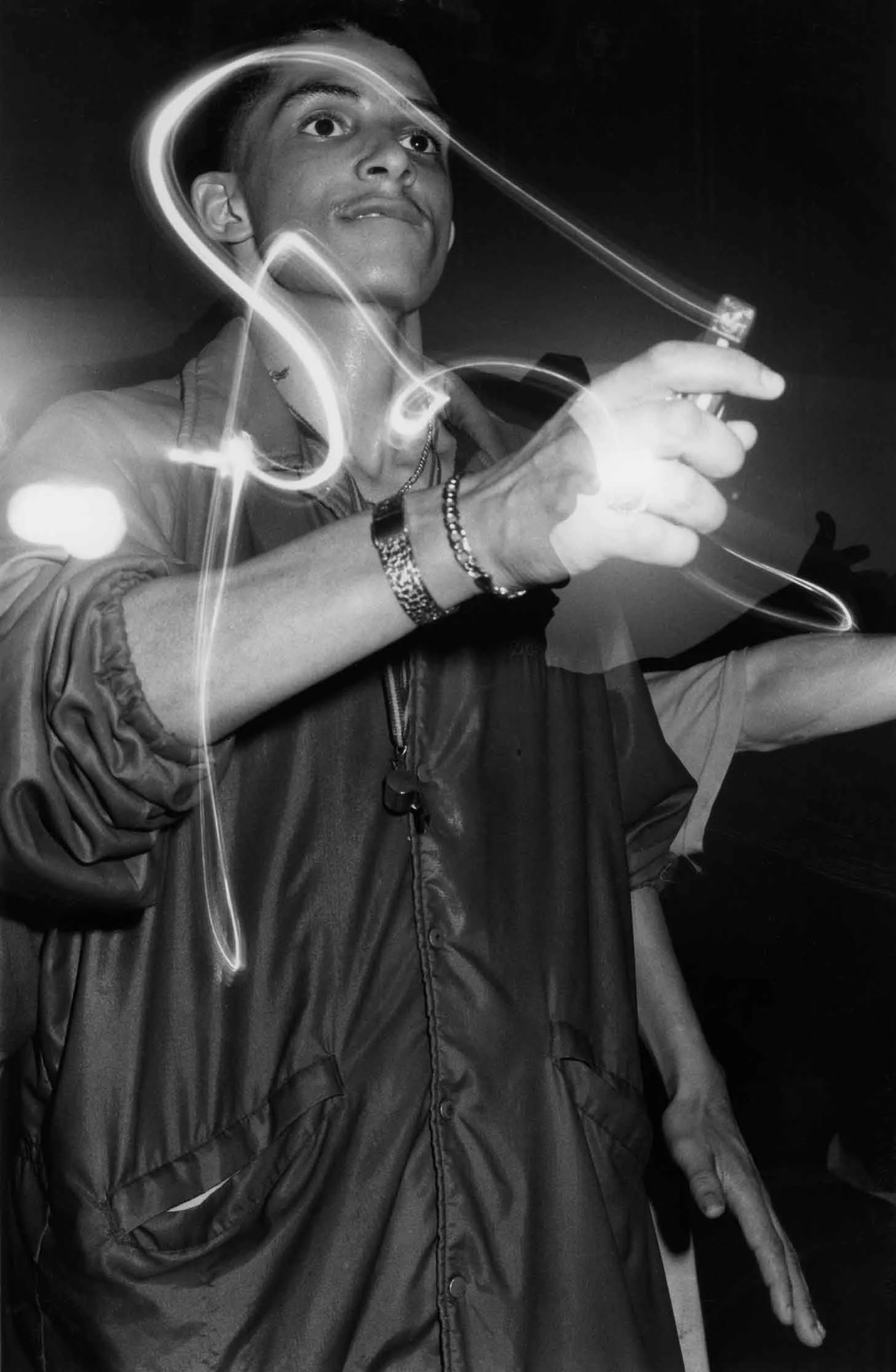

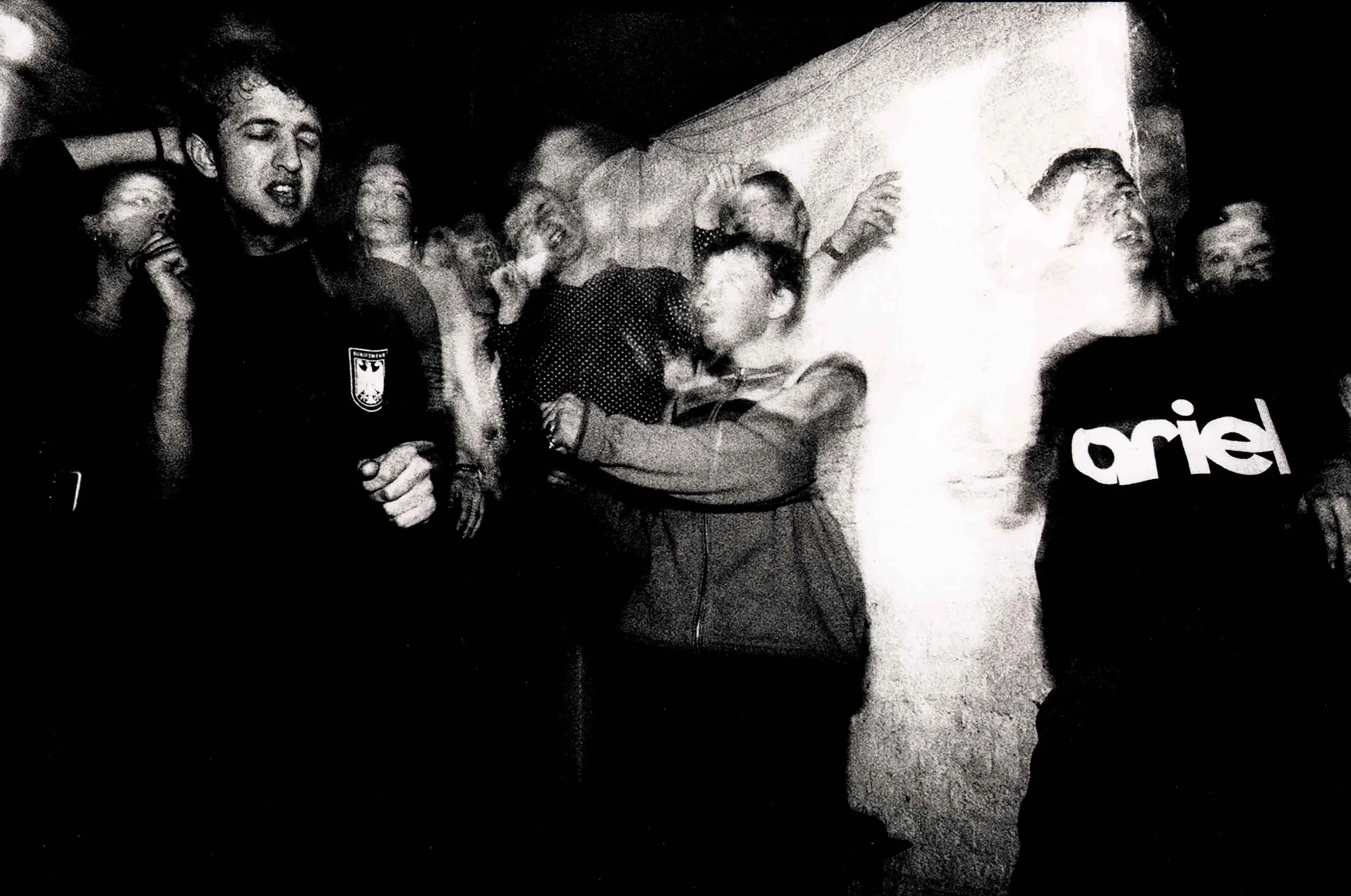

Davis is now widely recognised for his photographs of early 1990s rave culture - images charged with the sweat and electricity of a movement in its wild, euphoric infancy. He was never just a spectator. “People see me as a raver and a documenter of the rave, but I guess I was half in and half out,” he says.

His method was shaped by the limits of film and the discipline of documentary tradition. “I’d shoot 35 pictures in a day. I’d wait and wait and wait for something to happen. I’d move in close, keep the camera down, become invisible.”

In the darkness of clubs, he relied on single moments that were measured but laced with instinct. “Some of the rave images are just a single image… one flash and then gone. I left them alone.”

The photographs stand out today for their intimacy and absence of performance. In an era before camera phones, no one turned toward the lens.

“There is a lot of photography where people are aware of the camera.” Davis wanted the opposite: “I worked intuitively and unobtrusively.”

His images of club kids, ravers, football crowds and heavy-metal fans form a portrait of British youth culture at its most spontaneous - ecstatic, defiant, uncurated.

The rediscovery of his archive in 2020 was never intended as an artistic resurrection. He’d been teaching motorcycle mechanics, running workshops and juggling rent and bills. The pandemic caused teaching to be in something of a hiatus - at least in terms of being in the classroom. So, with one eye on a move out of London, Tony dug back into the boxes of old negatives and prints.

“In the end, I just thought ‘What do I do with this stuff?’… I thought ‘This will buy some bread and milk’.”

One of the first prints he pulled out was a photograph of DJ Norman Jay at Notting Hill Carnival wearing a T-shirt that showed a swastika-emblazoned effigy in a bin – a politically charged, joyous image of anti-racist activism.

“It was just an old print I found in the garage. I took an iPhone snap of it and put it on my Instagram and everybody jumped on it.”

Then came the rave images. “It’s the rave pictures that blew up,” he says. Messages poured in from old clubgoers: Did you go to this one? Was I there that night? Others arrived from curators and cultural archivists. “Having people from the British Cultural Archive getting in contact is a big honour - I would never see it as fame, but it’s recognition.”

Actors like Samantha Morton reached out - “she would just love the work and actually bought some prints, which was really sweet” - while musicians including Bobby Gillespie commented on his posts. Davis was touched and slightly bewildered. “I think I was a little bit overwhelmed.”

A salvage operation

Much of the archive had been scattered, returned unsorted from magazines, or simply lost in the churn of the analogue era. “The rave stuff is very messy… lots of stuff missing, lots of stuff lost.” Early-90s publications often mailed back contact sheets with images cut out plus the odd £40 cheque.

What survived has become a long-term excavation. “It has been a salvage operation, a rebuilding of what I’ve got. They could easily have all been thrown away.” Sometimes he finds gold by accident. “A couple of the Café Royal books I’ve done have been negatives I’ve found when I’ve been looking for something else: ‘Oh, there’s that sheet…’”

His archive now spans rave culture, football terraces (shot for When Saturday Comes and Four-Four-Two), heavy-metal festivals and everyday social documentary. He overshot on commissions, a habit that now pays off. “Monsters of Rock ’91 [featuring Metallica and AC/DC]… The Guardian only wanted one picture, but I shot eight or nine rolls. There’s enough for a book.”

Leaving London, Davis’s search for a new home led him to Thanet. “I know more people in Margate than anywhere else - there’s galleries, music stuff, people interested in the same things as me. So it seemed like a place to come.”

His ambitions are modest but heartfelt: more exhibitions, a few small books and zines of the archive and bringing more of the images to light. But the long-term plan is simple. “It is for my kids - they will inherit it and it will be protected.”

Today, Davis is often cited as an early practitioner of immersive crowd photography. The label makes him slightly uneasy. “I get referenced as a forefather, but I’m not an important photographer. I’m not prolific. I’ve got little pockets of images that are interesting to small groups of people. And I quite like that and I celebrate that.”

But the reaction to his work shows the emotional and cultural weight of his work. His pictures endure precisely because they are intuitive, unguarded and rooted in lived experience. They are not the product of algorithmic strategy or relentless self-promotion but of presence - being half in and half out of the scene.

INSTA: @tonydavisphoto