Nature’s Palette: Kent's Polben's Pigments extracts colour from the world

Pigment specialist Polly Bennett on shaving rust, super random sandstone and reviving the skill of extracting natural colour

Eucalyptus Bark Ash or Burnt Orange Brick may sound like the latest paint colour you’ve just picked up for the en-suite, but it’s unlikely to be created from its namesake source. Move over B&Q, we like to do things properly here.

On the endangered skills list, pigment-making is arguably something that most of those who create or appreciate art rarely consider.

Polly Bennett, an artist and pigment-maker from Rolvenden, has spent the last seven years studying the craft and producing hundreds of unique colours. Having launched online business Polben’s Pigments during lockdown, Polly has become one of the go-to sources of unique colours for artists and even takes commissions to create bespoke pigments.

“My most recent commission, I was asked to go to Jersey and collect from 16 sites various earth soils and samples, process them into pigments and then send them back to the artist to use,” says Polly. “The sites are from prisoner-of-war camps during the German occupation. There’s only one prisoner-of-war camp that’s currently marked on the island, while all the rest of them have been grown on or used as agricultural or residential land. The artist’s work is very much about the displacement of people and she’s looking at a way of commemorating these sites that have been forgotten about.”

“You just come across colours and then it’s about working out exactly how to extract it”

Polly’s own art practice has a very environmental focus to it and it was her upbringing in the west Kent countryside that eventually led her to exploring colours created from nature.

“I grew up here and I’ve always collected things that I found in nature,” she says. “When I went to uni in London, my practice was actually really figurative, it was all about drawing the figure, but I think subconsciously I really missed the landscape.

“I started collecting all these materials again and was kind of desperately searching for ways to reconnect with the land that I wasn’t surrounded by anymore. So my practice then really shifted and I wanted to look at ways of actually utilising the things I’d collected – and I guess one of the easiest ways to utilise these materials was to extract the colour from them.”

While Polly has used the waste plastic gathered from the Thames foreshore in the past in a wild form of recycling, the materials tend to consist of earth, bone, plant, shell and metal.

“With metal you’ve got straightforward rust, which you just shave off,” she says. “But then you’ve also got the copper oxidation, which is like the blue patina you see on copper pipes – you can shave that off and that gives you the pigment verdigris, which is like a beautiful blue-turquoise pigment.”

Polly has been known to burn down the bones of roadkill and the occasional Sunday roast to get to ‘bone-black’, while using vinegars and acids can help speed up the process in gathering a tougher-to-extract pigment. And then it’s a case of using the right ‘binder’ to ready the colour for use.

“Pigments are super-versatile – you could tint a varnish with them, you could use oil, you could use gum arabic for watercolour, you could rub them raw straight on to the substrate,” says Polly. “I would say I do have a lot of knowledge in pigment-making and a lot of it is just experimenting and practice so it becomes instinct to you.

“It is super-niche. Pigment-making is on the red list for endangered crafts. In America, it’s massive, there’s a whole community out there, but in the UK it’s still very specific.”

Polly, who is also manager at Gallery 35 in Cranbrook, hosts workshops across the county and into London for people to learn about pigment creation as well as the heritage of the skill – it even goes back to prehistory cave paintings.

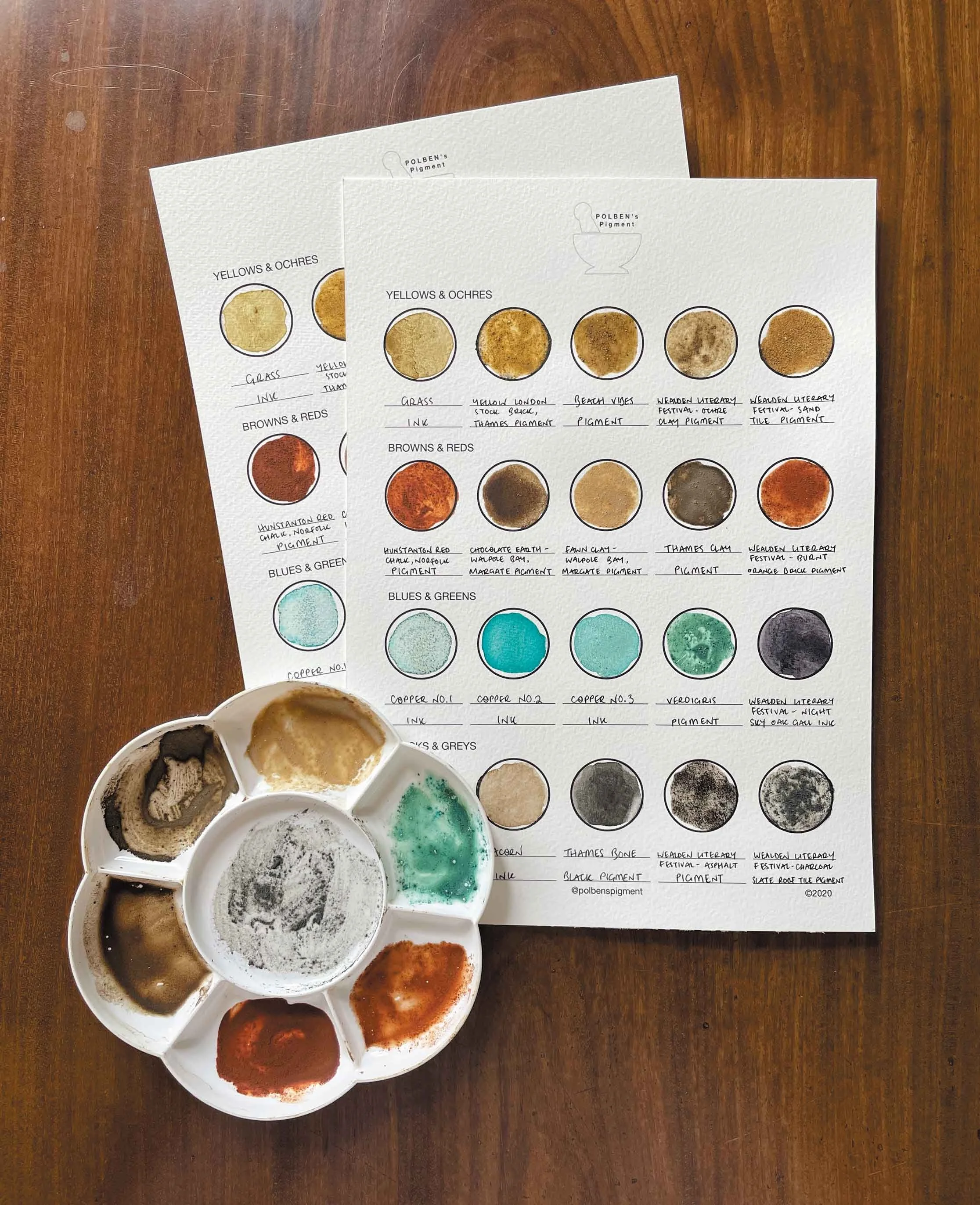

Documenting and recording pigments, their dates and locations, is also a crucial part of the process.

“Yeah, I have a vast archive,” says Polly. “I just like labelling things. It’s the autism in me. I just need to label everything. Everything has to be structured. I like to just know where it all comes from. I think part of the fun of it is like the discovery of where it’s from, the origin of place.”

And as Polly explains, while the back end of the process is structured and documented, the foray into the wild relies on its randomness.

“You never go out thinking ‘Oh, I’m going to find this today’. You just come across colours and then it’s about working out exactly how to extract it because different pigments have different extraction processes.”

Selling the pigments online, Polly uses a classic science-y look with glass vials and ink bottles sealed with wax containing the precious colours and, just like rare gems, the harder the colours are to extract, the cost increases.

“So verdigris, for example, that’s quite a waiting process,” she says. “So that’s probably one of the more expensive pigments – bone pigment and plant-based pigments also cost a premium just because it’s a longer process.

“But then your earth-based pigments are generally like cheaper ones just because they’re the quickest and most straightforward process.”

Of course, as with any discovery and creation, there are favourites.

“I think there were quite a few in St Ives that I found that I’ve never found again,” she says. “They were beautiful sparkly-green pigments in a variety of shades. They were super-random sandstone samples. So I couldn’t find their source or where they’d fallen from. They were really special.”

INFO: www.pollybennett.com