LOOKING FOR LOST - Interview with David Shillinglaw

Artist David Shillinglaw talks to Joe Bill about finding true abstraction, the purity of sketchbooks and his personal journey through space and time

It’s firstly really important to say that what you are about to read is an interview that has been monstrously trimmed down.

The depth and breadth of the subjects that David Shillinglaw (@davidshillinglaw) and I discussed would fill this magazine on its own - from cherry-pickers in Denver to ants at a picnic on a rock flying through space. It was both totally perplexing and wonderfully enlightening in beautifully equal measure.

The examination of your mind space, being lost and being present and even working out whether it’s better to be relaxed or to be freaking the f*ck out about the universe, are all oceanically giant subjects, but they all take place in David Shillinglaw’s sketchbook.

From his latest book Relax, The Universe is Expanding, we get a peek into drafts as the Margate-based artist tries to convey his journey as a human, first through paper and then canvas and then brick.

David is an internationally-renowned artist who has painted all over the world from Jordan to Ethiopia and Denver to Portugal, creating pieces that challenge and excite and occasionally overwhelm.

“In the last few years, I’ve been really interested in abstraction,” he says. “And trying to establish my own version of abstraction because abstract, like a lot of art, becomes derivative. Therefore, it’s not a truly abstract gesture, it’s an imitation of something. The challenge is for an artist to create their own language, in a way.”

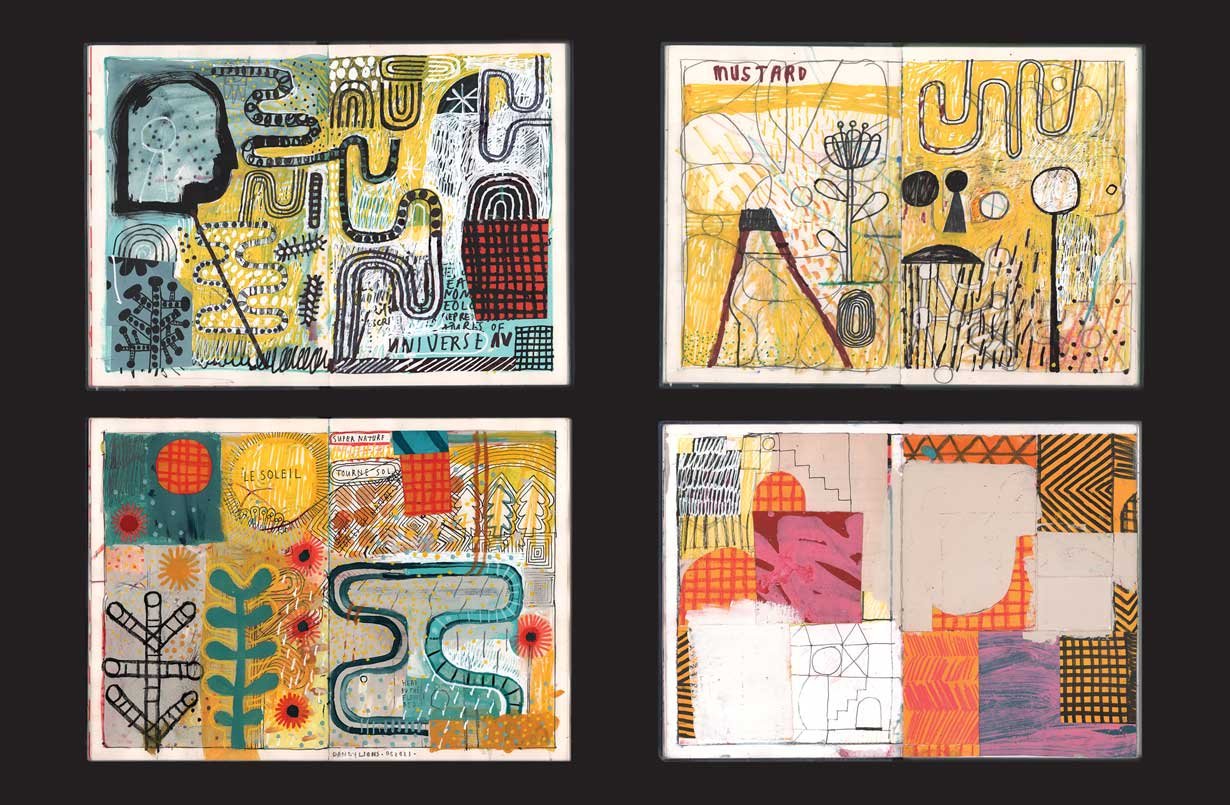

David uses his sketchbooks as his entry point to new work and ideas, inputting his thoughts and feelings of a specific moment, no matter where he might be.

“I’m constantly trying things out, whether it’s with colours, materials, gestures or lines,” he says. “One of the things I love about my sketchbook pages is that they are not designed. It’s kind of a strange obsession I have with my work, that I’m not trying to design something. But the sketchbook is the first place I try to make something happen, that I don’t know what it’s going to look like.

“I destroy things, I cover them up, I go over, I layer things, I delete things in a way that you can’t design - you don’t do it with a pencil and then colour it in.

“That might be quite an ugly thing. It’s not always something that I’m looking to be published. On the contrary, I’m looking for something that’s gonna surprise me. And then something will happen in my sketchbook, then ends up on a canvas.”

But not everything ends up on canvas.

“It’s impossible,” he says. “I’m forever trying to do on canvas what I’m doing with a sketchbook and I don’t ever quite manage it. There’s a reason for that - a sketchbook is paper, and canvas is canvas. The sketchbook is in my bag, I can pick it out at my kitchen table. My canvases, I have to turn up at the studio and it’s almost like getting into the boxing ring - you’ve got to put on the gloves and you’ve got to get ready. Whereas my sketchbook, I can pick it up while I’m waiting for the dentist. And I have it with me all the time. It’s an intimate space that you open and close - you don’t close the canvas. There’s also something about canvases being for sale - there’s this pressure to exhibit and to potentially sell it.”

TIME & SPACE

A recurring element of David’s work is what I described as a snake-type element that runs across his pieces. And it’s actually a key part of his translation of thought to visual representation.

“I would actually say it’s closer to a ladder or a train track,” he says. “It’s alluding to something that could be a snake, or it could be a ladder, could be a hopscotch, something that measures time. It’s me talking about a route, a line through something… these are things that are literal, but they’re also metaphorical because we’re all on a journey. We’re all climbing up certain ladders in life or falling down snakes.”

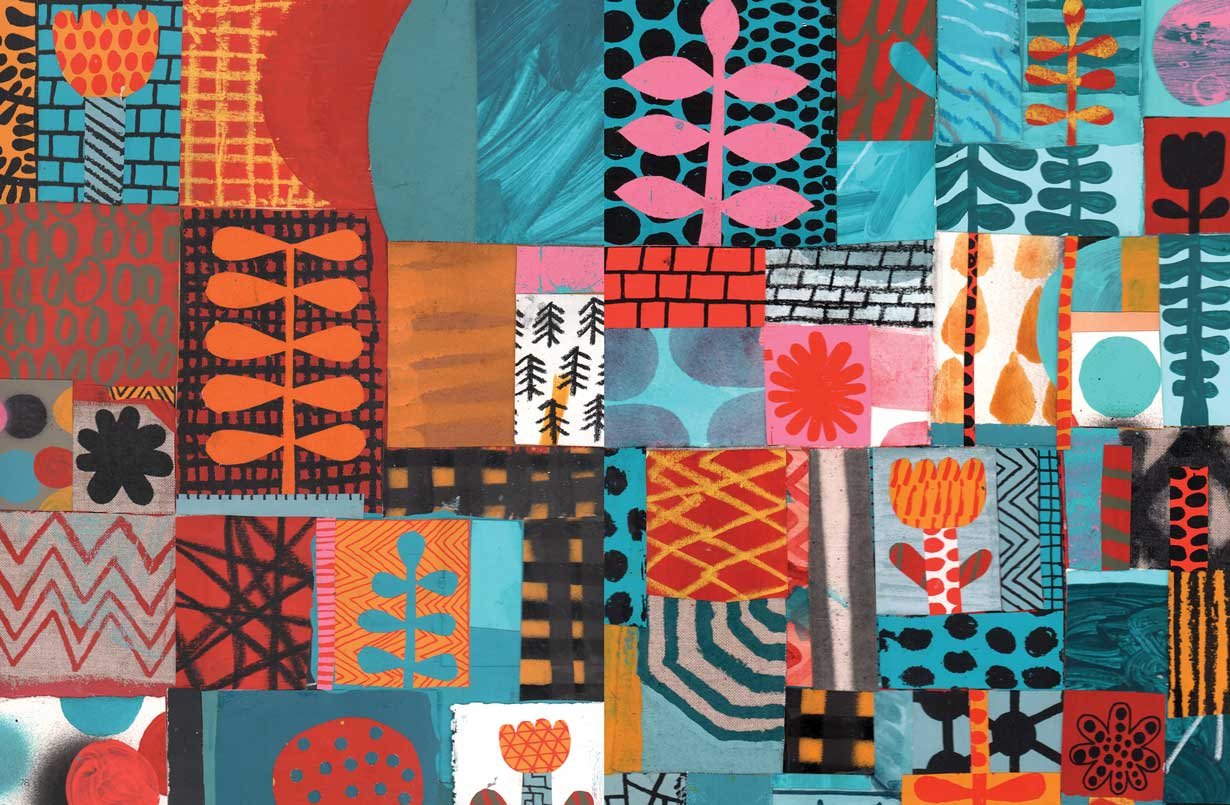

David references his recent works as being somewhere between a board game and a hieroglyphic.

“I’m playing with the language of board games, with segments, in a comic-book style. Patchwork sections for you to jump from one to the other a bit like a fucked-up psychedelic Monopoly board, like snakes and ladders on acid. Because I feel a lot like I’m walking through a board game.

“The way roads are even designed - they often say ‘don’t park on the double yellow lines’ or ‘click this to accept the cookies’. It all feels a bit like a computer game or a board game.”

Born in Saudi Arabia, growing up in London and moving to Margate from London, via just about everywhere, there is probably a good reason David’s work is also an examination of different types of spaces and how those spaces influence our lives. The very philosophical nature of our chat, and the delve into the neurological quirks that we all have sounds ultra-highbrow, but, far from sounding poncy, David has an amazing ability to bring it back to reality.

“I just assume we’re all on that journey to discover stuff,” he says. “And the language I use is definitely inspired by somewhere between doing mushrooms - not that I do that much anymore - and being fascinated with cognitive function, fascinated with my own but also everyone else’s brain. The human brain for me is as far-reaching and mysterious as the universe… that’s taken me many years to boil down what I’m interested in and how all of my work, whether it’s a portrait of someone or a sort of landscape, they’re just spaces.

“It’s debatable, but maybe all visual art is about spaces. Even if it’s a portrait of a king, or it’s Jesus on the cross, you’re talking about a space, you’re talking about the composition of the visual picture, you’re trying to record a space in time. And I guess the most personal to me, the most immediate is my internal space. It’s my brain, my fears, fantasies, grief, love, these things - the agony and ecstasy of being a human.”

There is no doubt that in thought and contemplation of our own existence, we could all get a little lost. In creating his pieces, and looking for ultimate abstraction, I asked David if he ever felt lost.

“Yes, and it’s interesting because right now I’m reading a book called The Field Guide to Getting Lost,” he says. “It’s really interesting you asked that because of the work I’m making at the moment, in terms of spaces, it’s an attempt to correlate or navigate between the internal and external space, my mind and my mental health.”

During the past couple of years, David suddenly lost his mother, experienced the birth of his first child and was locked down in a pandemic. He admits that at times it has affected his mental state.

“I was already a bit funky. And then those things have pushed me and pulled me into strange places sometimes,” he says. “Having a child is one of the hardest things to maintain and navigate. But there are moments of joy that you can’t explain to somebody who doesn’t have a child.

“But equally, if you try to explain to someone the feeling of grief when you lose your parent or a friend or anyone you love… it’s almost the other side of the coin. I don’t want to ramble on about birth and death as they’re obviously going to affect everyone. But going back to your question ‘do I ever feel lost?’ - yes. And I am interested in trying to celebrate the process of being lost.

“In my work, I’m trying to almost create spaces visually to get lost in. I want to invite you into my paintings to get lost. In the last few years, I feel more and more lost as I get older. Lost in grief, lost in joy, lost in the confinement of my home during Covid - lost in a sense of chaos, I guess. You’re not fully in control because you’re not when you’ve got a kid. And when you’re in lockdown, you’re not in control. When you lose a loved one, you’re not in control. So you might attempt to celebrate that lack of control.

“What I’ve realised is that sometimes when you’re the most lost, you can also be the most present.”

INFO: www.davidshillinglaw.co.uk