Maxim & Dan Pearce: THE HOPE PROJECT

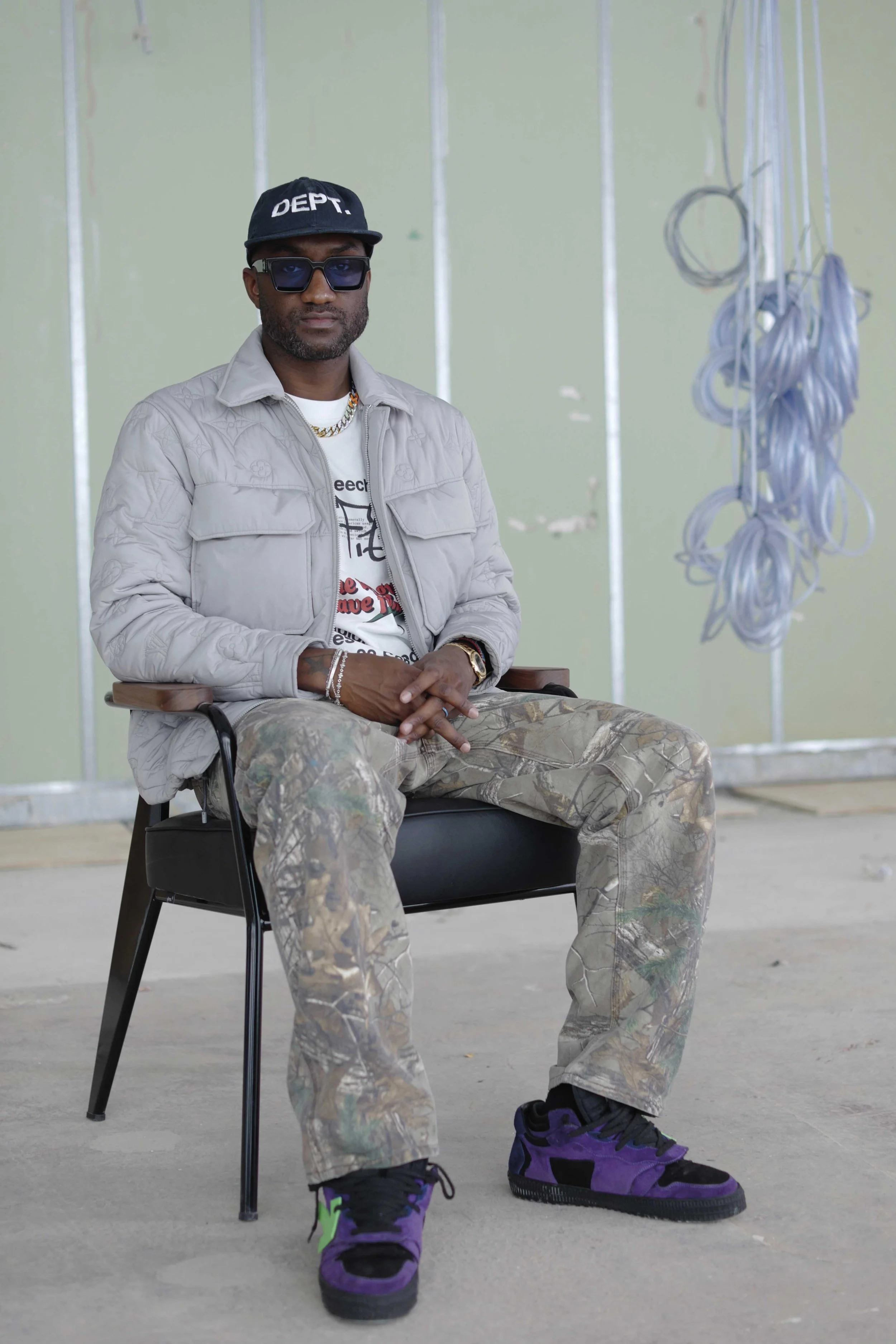

An exclusive interview with The Prodigy frontman and artist Maxim and mixed-media artist Dan Pearce as they collaborate on the powerful and poignant Hope project, writes Joe Bill

Acclaimed artists Dan Pearce and Maxim, also known as the frontman for The Prodigy, have spent a more than a year creating the ambitious, multi-platform collaboration, inspired by the ‘hope’ that everybody has been clinging on to as we gradually ease out of the devastation wreaked by Coronavirus.

Creating 50 limited-edition sculptures, the project contains an exclusive, four-track Maxim EP as well as the release of an accompanying short film, starring Pearce’s son Jackson, to tell the story behind the pair’s sculpture.

It depicts a little boy wearing a gas mask and preparing to pull the pin on a clear resin grenade containing a heart, which represents the vaccine and the hope that will help us navigate our post-lockdown worlds.

The grenade is a recurring symbol and theme in Maxim’s art, which includes highly sought-after paintings, prints and sculptures created during his 18 years in the art world. The pieces demonstrate Dan’s skills in 3D modelling and Maxim’s experience floating objects in resin.

Their short film touches on the mental-health implications the virus has had on children, showing Pearce’s 11-year-old son Jackson living through the pandemic. It also references the pandemic’s impact on homelessness – with a moving cameo from Maxim, playing a person living on the streets – as well as austerity, with touching food-bank scenes. Joe Bill (JB) spoke with Dan Pearce (DP) and Maxim (MM) to find out more.

JB

For people who don’t know, it’s probably best to start by explaining what the Hope project is...

DP

Well, myself and Maxim had wanted to do a collaboration for a while. But we are always busy with other projects. Being in lockdown provided an opportunity to do it and work together. We said the first thing we wanted to do for the brief was to create a sculpture that had a pandemic theme.

It’s about a boy who is struggling with mental health throughout the pandemic.

JB

Both of you have used mixed mediums in the past, so how did you decide upon a sculpture?

MX

Doing a painting is a different type of collaboration, but doing a sculpture… it’s putting your minds together to come up with an idea that is formulated ‘over there’. We weren’t sitting in a room together with clay, making something, saying ‘Oh, it’s my turn to spin the wheel’.

I was just getting into sculptures in a big way. I’ve done these cats with guns, Rebels with The Paws, and I was just in the process of forming the grenade with the heart in, so it was just to expand on that.

DP

With paintings it’s very 2-D. I’ve done collaborations with artists before and it is very much you do your bit and they do theirs, but with a sculpture it’s much more organic. You are moulding something together; it’s 3D and it’s got a story to tell.

MX

With any collaboration you have to be totally honest. It’s a coming-together. But if you feel it’s not working or not going in the right direction, you have to say. It’s a reflection of Dan and it’s a reflection of me as well, so it has to work on both levels. It’s months of to-ing and fro-ing, and finally you get to a balance and a place where you’re both happy.

DP

Yeah, it’s not like we kicked off with an idea straight away. It takes a lot of sketching and discussions and throwing ideas away and coming back with new ones... eventually you get to one where you hit the nail and you’re like ‘Right, this is it’. And you’re both excited about the same idea to move forward with.

JB

What came first, then? The film about the feeling of the pandemic, and then the sculpture? Or the sculpture that then bled into the film?

DP

The film was definitely secondary. We had created a story, without really knowing it between ourselves, about what the boy was, how he got there and what was going through his mind and what he was about to do. [The film] is something unusual to do to explain a narrative of a piece of art. I’m very much a believer that art is in the eye of the beholder and you shouldn’t need to explain, but for this piece we both agreed it was definitely the right thing, about how the boy got to that position.

MX

The basis of the sculpture is the grenade, and we know grenades are used in war. You throw a grenade, they are very destructive, it kills people. The whole concept behind the grenade is that it’s got a heart inside and you pull the pin, throw it and it spreads love and peace and harmony. So it was taking it out of its context and making it something totally new.

DP

We have been through the whole pandemic with the creation of it. As we were making the film, new things were coming to light, so we built the story about mental health within the child with what he was going through, and the film reflects that. We are trying to address what the issues were with the pandemic.

MX

If anything, the film brought things to the fore. It made me realise the things that get missed. Of course, there was a lot of focus on the NHS… but homelessness and children’s health were being missed. And the film helped highlight all these different things.

DP

One thing we really tried to highlight in the film was that Covid noise. That constant hourly report on radio and TV of words of death, death counts and staying indoors. And we wanted to highlight that in the film and how it’s affected the kids.

JB

Part of the piece is a four-track EP created by you, Maxim. Was that influenced by the pandemic as well?

MX

When I do art, I try to touch on so many different things. Like when I do an exhibition, I want it to be immersive. So it was the sounds, smells and temperature in the room. To play with all senses.

So, when we were doing the sculpture, I wanted to offer a four-track EP, but it’s like the soundtrack of the sculpture and the time. They’re quite orchestral and so forth, and just trying to create a mood of the image that the sculpture conjures up in my head.

JB

A lot of artists and musicians we have interviewed recently have talked about feeling very claustrophobic in the city during lockdown and wanting to get out, especially from London. Is this something you’ve experienced?

MX

I moved out of London a long time ago. But I’ve heard a few of my friends say exactly the same thing. I live in the country and I grew up in the country, so I appreciate trees and fields. I used to live in London, but it got to a stage where I was touring quite heavily and coming back to London, where it was just hectic, and I needed to get back out. I appreciate space and walking in my garden barefoot, and air and trees and plants. I can understand the situation for people who are living in flats, with no green space and just being locked indoors.

DP

My house is a Kent postcode and my studio is a five-minute walk into south-east London, so I’m on the border. But I grew up by the seaside on the Wirral. And it is something I do miss when I go home. But I keep hearing this term ‘reset’, where people have looked at their life and thought ‘You know, it’s not all about the rat race in London’. You don’t need to be living there now, we’ve all just proven you can do it from home. I completely see why people are having that life check and moving out.

MX

I really think that everybody went through such a traumatic stage in their life in the last year. There is a percentage of people who are going to have a reality check and analyse what life is about: ‘Man, it’s not about this, I need to simplify my life, I don’t need that and I don’t need that’. And then there will be a percentage of people who go back to normal.

JB

I think some people think that living in Kent, you’re going off to live on a farm, but you have Margate and Folkestone and all these creative towns where you can have that busy life but you are also next to the sea and the countryside and able to escape.

MX

I have a funny story about coming to the countryside. It was a long time ago. I think we were recording the Prodigy album Jilted Generation. There was a musician I took from London – I won’t tell you who – he lived in London and I brought him out to the country to the studio to record. As we were driving down the motorway, he said ‘What are those lights in the road?’. They were cat’s eyes. You don’t see cat’s eyes in London, do you! He was baffled.

JB

So, how’s it going to work with the sculptures – there are 50 of them, right?

DP

Three are going to charities we highlighted in the film: one to NHS Charities Together, one to young people’s mental-health charity YoungMinds and one to homeless charity Shelter. Some we’re going to give away to people who helped bring it all together, some we’re going to put into galleries and some we’re just going to keep. You do get quite attached to them.

JB

You both do so much art, how do you decide what pieces you’re going to keep?

MX

My house is actually full of my art. The reason I got into art 18 years ago is because I needed art for my house. I went to an affordable art fair, saw what they were doing and thought ‘I could do that’. So, I went home and started painting. I’ve got quite a few of my sculptures. But yeah, you do get attached. It’s not just memorabilia in some respects, it marks a point in your life in creativity. It’s always something I treasure.

DP

My house was full of my art and then for the last three years I’ve become a big collector of other people’s art. Now I’ve only got one piece of my art, which my wife likes and that I’ve kept.

The other bits are random pieces, but they’re swapped quite regularly.

JB

This sounds very corporate, but do you think there is a synergy between the worlds of music and art?

MX

Well, music is art. But, to be honest, at the start I tried to keep them very separate. I found people quite sceptical when you did art and music. But now I talk about it in the same way, it’s part of me. We are all creatives in this space, whether it’s music, art or fashion. It’s just creativity, it’s all embroiled in the same thing and now I don’t separate the two.

JB

Finally, what have you got coming up? Obviously with the last two years, the passing of Keith Flint and the pandemic, what does the next couple of years look like for you?

MX

For me, I’m really concentrating on my art. But obviously it has been a tragic time the past two years with Keith, and the pandemic has come at a weird time and closed everything down. It’s kind of given me some breathing space and I’ve been more of a recluse than anything, but it has given me space to do my art and focus on being myself. Next year, who knows? The Prodigy might be back out again. We’ll see.

INSTA: @maxim & @dan_pearce _art