Sailor's Mark

The relationship between British Maritime and Skin illustration is explored as the ‘British Tattoo art revealed’ exhibition sails into The Historic Dockyard Chatham

PHOTO: LUKE HAYES / COURTESY OF NEIL HOPKINS.

From the sexy sailors of the famous Jean Paul Gaultier advert through to Popeye’s pulsating forearms, the ink link between maritime heritage and tattoos is there in popular culture for all to see.

But while the vogue of skin illustration has exploded in recent years, pushing ink into the worlds of fashion, sport and music, the history of the UK’s relationship with the art form – at least in common knowledge – has faded to a dull blue.

This summer, for the first time, the Historic Dockyard in Chatham will be exhibiting the nautical knot formed between the sea and the needle, busting open the myths and revealing the truth behind all those swallows and anchors at Tattoo: British Tattoo Art Revealed.

“There is an undeniable link between tattooing and the sea,” says Derryth Ridge, co-curator of the exhibition, created by National Maritime Museum Cornwall.

“Sailors would have used the same needle they repaired their sails with to prick their skin and mark their bodies, whether that was to remember someone back home or to show allegiance to crown and country. For me, tattooing is all wrapped up in romance and patriotism. Taking your sweetheart’s name with you under your skin must have felt like it was tying you back to shore.”

Running in the No.1 Smithery gallery from Saturday, March 21, to Sunday, June 14, the exhibition offers a comprehensive history of British tattooing, featuring cutting-edge designers, leading academics and major private collectors to tell a story that challenges preconceptions about tattooing when it comes to class, gender and age while at the same time giving a voice to and celebrating the astonishingly rich artistic heritage of tattooing as an art form in the UK.

PHOTO: LUKE HAYES / COURTESY OF NMMC.

It will showcase the work of tattoo artists from George Burchett, via the Bristol Tattoo Club, to Alex Binnie and Lal Hardy and is the largest gathering of real objects and original tattoo artwork ever assembled in the UK.

“It is a hugely rich and vibrant part of our social history,” says Ridge. “We really wanted to highlight the artistry in tattooing and to challenge people’s perceptions of the people who were tattooing and those who were tattooed.”

Tattoos are a living and uniquely three-dimensional form of art. The exhibition has responded to this with an innovative installation that literally brings the art off the gallery wall to create a ‘sculptural map’ of British tattoo art today.

The 100 Hands Project, curated by Alice Snape of Things and Ink magazine, is based on one hundred silicone arms, each tattooed with an original design by 100 of the leading tattoo artists working across the UK. The exhibit creates an important artistic legacy for future generations – an archival ‘snapshot’ of a form of art all too often lost to the ravages of time.

“We were incredibly honoured to receive the backing and support of the industry,” says Ridge. “People were cautious to begin with, they were concerned that the exhibition would be sensationalist or tokenistic. However, were worked alongside tattooists, collectors and academics in the field to create a truthful and engaging exhibition that pays respect to this wonderful history.”

The exhibition also includes contemporary art commissions from three tattoo artists working in three very different tattoo traditions. Each artist has created a unique design on a hyper-realistic body sculpture that speaks to the historic artefacts and artworks around it.

Tihoti Faara Barff’s work celebrates the modern revival of Tahitian tattooing; Matt Houston’s commission is a heroic celebration of the sailor tattoo; and Aimée Cornwell, a second-generation artist and rising star in the tattoo world, illustrates how tattooing is breaking down artistic boundaries with her own form of fantasia.

Ridge highlights the story of Jessie Knight, the self-proclaimed First Lady of British tattoos, as something not to miss.

“She is a feminist icon and was a real pioneer for women working in the profession today,” explains Ridge.

The exhibition features items from three of the most important private collections of tattoo material in Britain, belonging to Willie Robinson, Jimmie Skuse and Paul ‘Rambo’ Ramsbottom, providing a rare opportunity to display original artwork and artefacts not otherwise on public display.

FACT BOX

A rooster or pig decorating the calves or feet was thought to ensure safety at sea, probably because these animals (travelling as they did in lightweight wooden crates) often survived shipwrecks.

A swallow was to show the person had sailed 5,000 nautical miles. An anchor was to show they had sailed the Atlantic A turtle standing on its back legs, or King Neptune, was linked to crossing the equator

A dragon represented sailing to China.

Some tattoos signalled a specific job role. A dock worker, for example, might be decorated with a rope around the forearm, a member of the fishing fleet might sport a harpoon, while guns or crossed cannons indicated military naval service.

INK LINK.

It is estimated that about one in five of the UK population is tattooed and this figure rises to one in three for young adults.

“I think that tattoos have become more mainstream and people aren’t scandalised by them as they may have been 50 years ago,” says Ridge. “It used to be that there would only be one person tattooing in a town, so there just weren’t as many tattooed people. There are so many great artists out there now, and more people are getting more visible and more heavily tattooed. Social media and celebrity culture give us intimate access into people’s lives, so we’re more aware if people have tattoos.”

And yet, while the visibility of tattooing in contemporary culture may feel like something new, tattoos and tattoo art have always held a significant place in Britain’s history and historical imagination.

The exhibition explores this history in depth and shows that while the word tattoo may have come into the English language after Captain Cook’s voyage, this was not the start of the story of British tattooing.

Amy Welsh, head of visitor experience at Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust, said: “There are long-established connections between seafaring and tattooing, and this exhibition gives a rare opportunity to explore these links through some exceptional exhibits and displays.”

PHOTO: LUKE HAYES / COURTESY OF NMMC.

One of those locally related displays will be from within the Dockyard itself. Artist Fraser Peek has a tattoo studio on-site in the Joiner’s Shop, and the Dockyard has been working with him to create a Dockyard tattoo in celebration of the exhibition.

Another Medway connection comes in the form of Charlie Bell. Charlie tattooed in Chatham in the early 1950s and his family still work in the tattoo industry, with a studio in Rochester. The Dockyard is working with them to launch a public appeal for any stories and pictures of Charlie Bell tattoos they can use to create an online exhibition of his work as well as archive the work into its collection (keep an eye out on its website for more information soon).

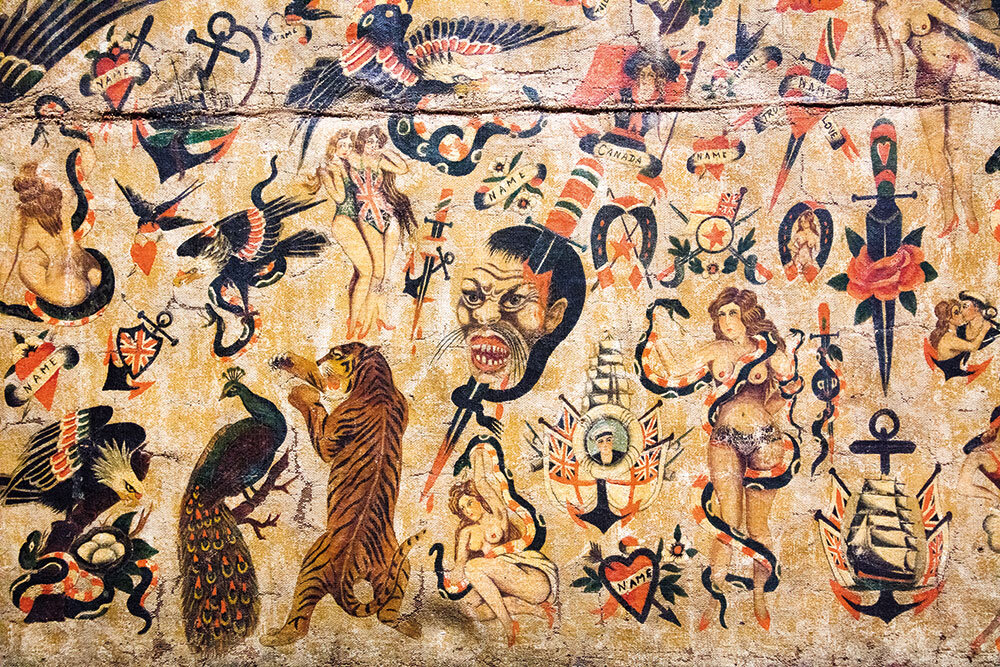

“The exhibition has something for everyone,” says Ridge. “It’s a proper social history, telling the stories of tattooers and the social impacts of tattooing throughout history. The flash [the sheets of tattoo designs] on display are rich and beautiful, a true art form.”